When a premier ends and people clap for a very good film. Then, why does one sit in stunned silence, rather than join the audience? This question hit me after watching The Bengal Files. Because I was not just looking at the craft of the movie alone. The movie left me pondering about the real lives impacted by the violent partition of Bharat and a cruel episode in history that has been wiped clean by our Sarkari historians and from the collective psyche by the Bengali intellectual class.

Why did our leadership decide to suppress the horrible history of Partition? Why did Leftists and Secular historians try to whitewash this chapter? Does applying band-aid to a deep wound cure the wound or lets it fester and turn into a gangrene? This is essentially the question that the young officer asks his boss. He questions him, why every crime and problem is turned into Hindu-Muslim issue?

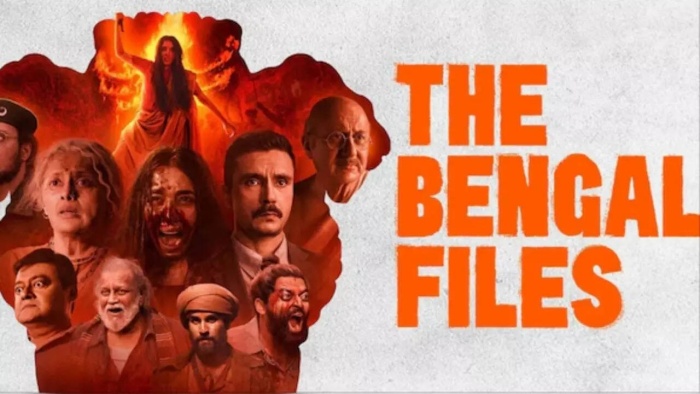

The Bengal Files has a better screenplay than The Kashmir File. The idea of bringing in the chief protagonist of this movie from The Kashmir Files is a brilliant idea. It gives the narrative a kind of continuity, and at the same time highlights the fact that day before yesterday it was the Partition of Bharat, yesterday it was Kashmir, and today it is Bengal. Ironically, facing the same situation it faced in 1946. The horrors of exclusivist religious extremism are a continuing thread, not isolated incidents.

The story moves back and forth between the fateful months prior to August 15, 1947 and the current minority driven politics of Bengal. The character holding the past and the present together is the character of Bharati Banerjee, played hauntingly by Pallavi Joshi. It is an outstanding performance that could win her multiple awards. Well, maybe not, because the award distributing lobbies are controlled by the same secular groups that control academia, and till recently media. Only by the end you realise that Bharati, actually, symbolizes traumatized Bharatmata.

Characters that were unknown for the lay people, like Gopal Patha and brave freedom fighters of Hindu Mahasabha come to light as you never knew about them. The idealist Gandhi ji feeling lost in the violent days of Kolkata and Noakhali with confused thinking, spouting ‘benign advice’ for the women of Bengal who were being kidnapped and raped, tired Congress leaders unable to resist the carrot of early declaration even if it meant partition of a thousands of year old nation at the cost of blood riddled partitioned Bharat, trouble you. The disunited frightened response of the Hindu community during 1946 against the violence makes you ponder. If you have read the this part of history, it readies you for The Bengal Files. But watching it on screen hits you hard. You have not seen such brutality in your lifetime, your forefathers who saw it, mostly did not tell you their stories.

Many dialogues of this movie have potential to become iconic, like the dialogue of The Kashmir File – “Sarkar unki hai, par system hamara hai.” I have hardly heard more direct, and unapologetic dialogues about Hindu-Muslim relations, and about artificial façade of secular peaceful and loving relations built on ‘Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’. We have fidgeted nervously when someone speaks about these issues. However, one must confront the reality. Those who are nervous of their vote bank politics getting exposed under the full flare of film screen will naturally want to ban this film. The secular leaders of Bengal, whose followers tell us, “Don’t watch it if you don’t like it.” But when shoe pinches their collective dead conscience, they go dumb.

It is difficult to get actors for such movies. So, with his intrepid band of well proven veteran actors who can leave behind a big impact, Vivek Agnihotri uses fresh faces. Advantage is that the new actors become the real-life characters. Monologues of the Krishna Pandit played by Darshan Kumar with conviction are some of the highlights of the film. His impotent rage of a person bearing with injustice all his life, who finally breaks the shackles of “ghulami” gives a life of its own to the film. Mithun Chakraborty, Anupam Kher, Rajesh Khera, Mohan Kapur, Namashi Chakraborty, Mohan Kapur, Saswata Chatterjee et al all play their roles with finesse, painting new shades to their characters. Simratt Kaur looks ethereal as young Bharati Mukerjee and has the biggest and the toughest role, with whom you empathize. I wish it had been done with a little more depth and fire.

Background music haunts you and lifts the movie up a notch and evocative use of well-known Bangla songs heightens the emotions. Vivek Agnihotri has spared no expenses to create the period feel with huge sets. Cinematography is able to capture the period and the mood well.

This movie shatters your delicate sophisticated self-image of a peaceful society living under the umbrella of benign secularism, and ahimsa, and your assumptions. All these shattered glasses in your front make you uncomfortable. But uncomfortable one must be, if one does not want history to repeat itself as a farce, as it is happening now; or a tragedy that awaits us unless we find honest solution built on mutual trust and pragmatism. Unless we face the truth, howsoever uncomfortable, and seek reconciliation based on acceptance of real history by all concerned, we cannot attain a peaceful and happy society. World over, countries have done it, communities have done it. The movies on Jew Holocaust have not resulted in riots, they have resulted a more sensitized society. Showing Blacks and Natives in poor light did not bring peace to America, acceptance of their brutalization has sensitized their people and solutions are being found. Don’t blame Vivek Agnihotri, blame the fake narratives. He is only showing us the mirror to spark the process of catharsis.