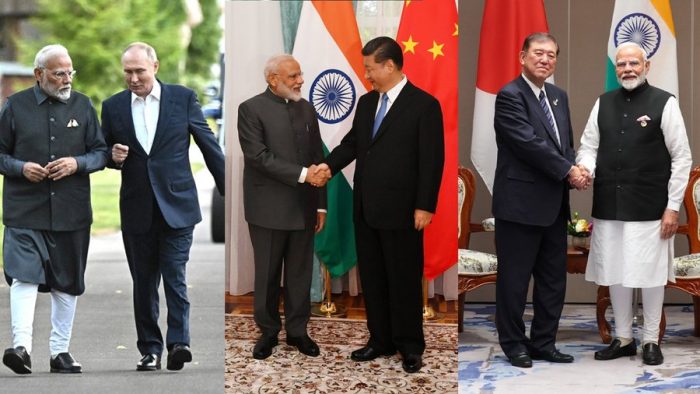

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s back-to-back visits to Japan and China come at a critical time for the global economy. Washington establishment under Donald Trump’s presidency is getting apoplectic as India tests a cautious thaw with Beijing and strengthens supply linkages with Japan.

In the recent outbursts of Peter Navarro, senior counselor for trade and manufacturing to Trump, he has been accusing India of supporting Russia’s war. He even dubbed Russia-Ukraine war as “Modi’s war,” and tried to explain the 50% tariff shock while publishing a photo of Modi in saffron to insinuate sectarian politics. The optics are unappealing, the economics are shoddy, and the plan is counterproductive. India is under no obligation to act as someone else’s proxy. It is developing an Asia-first economic map, with Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest trading bloc at the core and re-entry remaining a viable option if circumstances are favorable.

Japan: Partnership beyond optics

In Japan, Modi is prioritizing substance over symbolism. De-risking supply chains and securing long-term capital in India are the goals of the visit aiming for advanced manufacturing, semiconductors, essential minerals, high-speed rail, and defense industrial cooperation. In addition to Japan steadily investing in Indian capabilities, including ports, freight routes, urban transit, and now next-generation technology. Tokyo is also the only partner that supports India on the China problem.

“Make in India, Make for the World” was not merely a slogan when Modi made his pitch in Tokyo this week. It was a market invitation supported by demand, demographics, and policy changes. Japan serves as India’s industrial counterbalance, preserving the QUAD’s economic backbone and lowering its susceptibility to tariff wraths abroad.

In order to secure its growth trajectory, India should embrace the East Asian strategic geography and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), according to economist Jeffrey Sachs. Japanese FDI and co-production can lessen the impact of Washington’s harsh tariffs, particularly in industries where American companies are sluggishly sharing technology. India’s position in any future RCEP discussions is further strengthened by a more robust Indo-Japan production network.

China: Engagement without illusions

The China stop is practical compartmentalization, not surrender. While pursuing trade, investment, and market access victories that promote expansion and export volume, New Delhi can maintain a strict border and security stance. Because the scale of Asian demand is too great to ignore, the choreography is purposeful; it begins in Beijing and continues to intensify with Tokyo. Some people in Washington are uneasy about that because they want India to be permanently aligned against China. That won’t happen in India and it hasn’t. It favors bilateral connections for trade, SCO/BRICS for hedging, and issue-based coalitions like the Quad for security. In the short run, China will have impressive optics as Xi hosts Putin and Modi to portray a non-Western center of gravity.

What Washington gets wrong and why Navarro is the worst messenger

With the nuance of a sledgehammer, Peter Navarro has made a comeback to the public eye. He has defended 50% tariffs on Indian goods, referred to the conflict in Ukraine as “Modi’s war” in interviews and on X, accused India of operating a “laundromat” for Russian oil through refined products, and, tellingly, ended his thread with a picture of Modi wearing saffron, suggesting that India’s policies are motivated more by sectarian nationalism than by pragmatic economics. That is crass, reductionist politics posing as strategy.

Unpacking the errors by Navarro

- Energy security is not Warmongering – After 2022, India increased its purchase of Russian crude to maintain price stability and inflation management. That decision is motivated by consumer welfare and grid dependability, not geopolitical allegiance. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, G-7 implemented a $60-per-barrel price cap to reduce the Kremlin’s oil revenue while assuring global supply. India’s capacity to purchase cheaper cargoes was a component of that process, US officials admitted.

- Tarriff blackmail doesn’t build alliances – A domestic base may be appeased by imposing a 50% tariff and taunting India on TV/X, but doing so reduces U.S. power, forces India to increase its efforts in Asian markets, and increases the appeal of Japan-India and RCEP-plus options.

- The saffron image is a tell – Ending a policy thread with an image of Modi in saffron is not analysis, it’s a dog whistle designed to portray India’s choices as sectarian. That is not how you communicate with a sovereign partner you claim to respect. It has sparked reaction across the Indian political spectrum.

In summary, Navarro’s strategy is both rhetorically and economically inflammatory. It seems that some people in Washington would prefer to penalize India rather than work with it on issues like price ceilings, rules of origin, or integrated energy management areas where real policy is made.

RCEP: The Asian trade engine

This brings us to the economic map’s center. RCEP 15 Asia-Pacific economies led by ASEAN, which include Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and China, account for about one-third of world GDP. India left the bargaining table in 2019 due to worries about Chinese dumping, rules-of-origin violations, and inadequate service access. These concerns were genuine. But the world has moved on.

The RCEP came into effect in 2022, and its tariff phase-downs and cumulation procedures are already reshaping Asian supply chains. With fresh US tariffs in place, Delhi is openly reconsidering whether a guarded re-entry is better for Indian exporters than staying out.

India famously withdrew from the 2019 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) talks, saying that it was concerned that low-cost imports, especially from China, would overtake homegrown industries and cause disproportionate harm to vulnerable sectors like dairy and agriculture. India’s primary concerns were not addressed, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi remained steadfast. The country’s farmers, micro, small, and medium-sized businesses, and dairy industry were helped with the decision to not join RCEP.

Meanwhile, Japan, Korea, and ASEAN members are already benefiting from expanding RCEP preferences and cumulation among themselves, leaving India vulnerable to trade diversion if it continues to be outside the pact.

Potential re-entry does not necessarily imply “open borders” liberalization. It can be conditional integration, with snapback safeguards to protect sensitive sectors like agriculture and dairy while utilizing the advantages of RCEP in supply chains, manufacturing, and technology. There can also be tough rules of origin to prevent Chinese trans-shipment via third countries.

At a time when Washington’s tariff rants threaten India’s exports, such a plan not only protects rural India but also enables New Delhi to optimize market access in Asia. In other words, India can protect its sovereignty and thwart American pressure by shielding farmers at home and merging industrial sectors outside.

When done well, RCEP is less of a capitulation and more of a tool for India to gain strategic economic scale while hedging risks by design, regardless of whether US goodwill follows.

Why some sections in Washington are going mad against India

Remove the noise, and three distinct worries explain Washington’s outburst. The first is a loss of trade leverage, if India anchors supply chains with Japan and considers a cautious re-entry into RCEP, the US loses the tariff stick it used to win concessions, which explains the pressure tactics and exaggerated fury over India’s oil purchases. Second, the battle for narrative control, branding the Ukraine crisis as “Modi’s war” is an attempt to rewrite causation, shifting responsibility for a European conflict onto an Asian democracy practicing energy pragmatism inside a sanctions regime established by the West itself.

Third, there is concern that an Asia-centric order may emerge without Washington at the helm. Xi Jinping hosts both Putin and Modi, and Tokyo and Delhi strengthen industrial links, a non-Western geometry emerges which the US must learn to navigate rather than dictate. Tariffs and insults are a bad place to start.

Conclusion

China’s vast theater and Tokyo’s boardrooms, Modi’s twin visits, show a self-assured India laying out its own economic routes and security measures. In that scenario, RCEP is a platform that India can influence if the conditions benefit its producers and consumers rather than a sign of surrender. The United States has two options: either accept India’s reality or lash out against it on X threads and on TV channels. Peter Navarro opted for the latter, slipping into satire with saffron imagery and catchphrases that dissolve under scrutiny. India does not have to give a reciprocal response. It needs to keep pushing Make in India, trade with Asia, and deal with America on equal terms. India’s eventual independence is the reason why some elements of Washington are “going mad.”