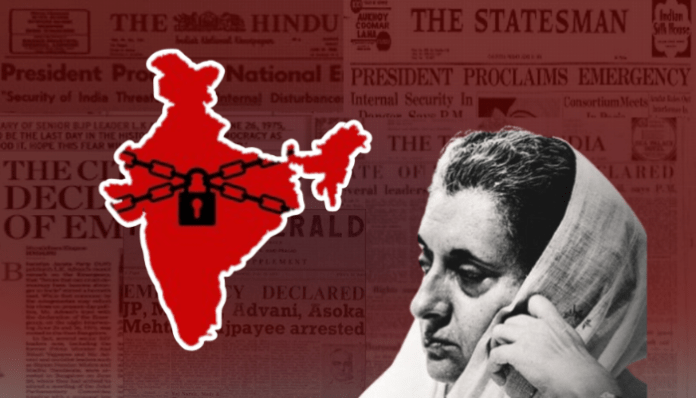

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the Emergency proclaimed by Indira Gandhi in 1975—a year etched in black ink for the nation, as it curtailed the freedoms of its people. Several events unfolded during that period which led to the imposition of Emergency on the midnight of 25 June 1975. That night turned into a nightmare, as the nation woke up to a bombshell from the Allahabad High Court, which found Indira Gandhi guilty.

India was governed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmad when the Emergency was enforced under Article 352. The move was justified by citing internal disturbance and a threat to national security. Between the proclamation and 1977—nearly two years of unrest—the nation faced numerous challenges: civil liberties were suspended, opposition leaders jailed, press freedom was curbed, public gatherings banned, and much more. Although India remained a democracy on paper, it felt stripped of its identity for the next 21 months.

While every decision deeply unsettled the nation, the censorship of the press was especially disturbing. The press was silenced overnight. Power supply to newspaper presses in Delhi was cut immediately after the Emergency was declared. Mainstream media such as The Indian Express resumed publication with its June 28 edition, leaving a blank space in the editorial section. The Statesman followed with similar blank columns. The National Herald, founded by Jawaharlal Nehru, faded out its masthead slogan: “Freedom is in peril, defend it with all your might.”

The Indian media was instructed that all newspapers must seek approval from the Chief Press Adviser before publishing anything, and were barred from sharing any content that could spark public outrage. In fact, Indira Gandhi issued a set of guidelines for journalists, making it mandatory to adhere to them.

While mainstream media gasped for air, vernacular newspapers struggled to hold on to their identity. People continued to rely on regional publications for news. Newspapers like Frontier, Sadhna, Janata, Himmat, and Swaraj quickly fell victim to censorship. Ranchi Express, the only newspaper in the then-united Bihar, which began in 1963, left its editorial space blank—carrying the censor officer’s signature—a fact documented in the book Emergency Ka Kahar Aur Censor Ka Zahar.

Gour Kishore Ghosh, a satirist and editor, was jailed after he shaved his head and published a symbolic letter mourning the loss of freedom. Bartaman—founded later by Barun Sengupta—reflected that enduring spirit of dissent, even though it came post-Emergency.

The restrictions were so severe that the press was barred from covering major news. In mid-1975, Sanjay Gandhi launched a Five-Point Programme—family planning, abolition of dowry, eradication of illiteracy, elimination of casteism, and a plantation drive—perhaps to distract the public from the Emergency. Journalists were strictly banned from reporting or photographing the slum demolitions at Delhi’s Turkman Gate, which rendered thousands homeless. Coverage of the conditions inside the high-security Tihar Jail was also off-limits.

Foreign journalists from The Times, Newsweek, and The Daily Telegraph were given just 24 hours to leave India if they refused to sign censorship agreements. While the Indian press remained under government surveillance for 21 months, the foreign media found opportunities to expose the real state of journalism in India and the suspension of constitutional rights.

According to Om Mehta, the then Home Minister, nearly 7,000 journalists and media workers were arrested by May 1976.

The English weekly Himmat, started by Rajmohan Gandhi, faced intense backlash and initially left its editorial page blank in protest. Later, the publication resumed its regular tone, only to be informed it had violated censorship norms. Rajmohan Gandhi and his brother Ramchandra Gandhi were soon arrested after covering a prayer meeting at Rajghat on October 2, where Acharya J.B. Kriplani had spoken. They were later released.

Veteran politician L.K. Advani’s famous remark—“You were asked only to bend, but you crawled”—still echoes in the conscience of Indian journalism. He too was imprisoned during the Emergency. Noted journalist Kuldip Nayar was also arrested for raising his voice in protest.

Even before the ink had dried on the Emergency declaration, Punjab Chief Minister Giani Zail Singh called N.P. Mathur, the Chief Commissioner of Chandigarh, urging strict action against the press. He demanded that The Tribune, a leading newspaper in Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu & Kashmir, be shut down, and that its editor, Madhavan Nair, be arrested. Mathur found himself in a bind—he didn’t want to issue official orders. Instead, he relayed the message to S.N. Bhanot, the Senior Superintendent of Police. However, Bhanot refused to act without written instructions from the District Magistrate. Still, he visited The Tribune‘s office and warned the staff not to publish content that could displease the government. A small police team was also stationed there.

But The Tribune did not back down. The paper hit stands the next morning as usual. This infuriated Haryana Chief Minister Chaudhary Bansi Lal, who threatened that if the Chandigarh administration didn’t raid The Tribune and arrest its editor, he would send the Haryana Police to do it himself. But that too didn’t happen—civil servants stood their ground and refused to carry out unlawful orders. Ultimately, they only appointed a Censor Officer under the Defence of India Rules.

In Jalandhar, Hindi and Urdu newspapers printed blank pages with the label ‘Censor ki Bench’. Veer Pratap, a Hindi daily from Jalandhar, was even more expressive, printing an Urdu couplet beneath its empty editorial space: “I can neither anguish nor petition; it is my fate to choke and die.”

The government later labelled this period as ‘Samvidhan Hatya Diwas’—a time that may have tested the nerves of Indian citizens, but did not break them. Despite the heavy censorship, what remains crucial to remember is that Indian newspapers and media outlets kept breathing. With the rise of independent and digital media in the 21st century, the ability to report truth has only strengthened—offering the people easier and broader access to information than ever before.